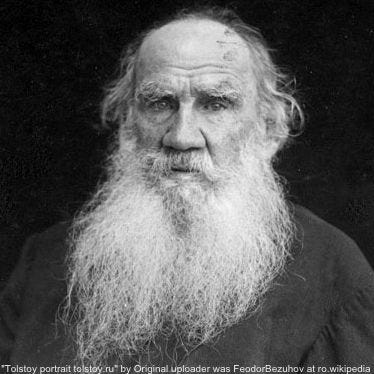

A Defense of Dostoevsky Against David Bentley Hart

Tolstoy is much better at writing normal people. But Dostoevsky writes people like me. Both are "real" people.

At the outset, let me say that David Bentley Hart is my favorite contemporary thinker. His work did not so much teach me about classical theism and its moral vision of the world, as it did confirm it. In my younger, insecure years, I needed this confirmation badly, and Hart's work has been extremely helpful in quieting some of my angst. In this dispute, I do not disagree much with Hart, but want to push back a bit on his characterization of Dostoevsky's writing of his characters.

Hart’s Claim: Tolstoy is a Better Artist and Character Writer

I was recently surprised, after having immersed myself in Dostoyevsky over the past year, to find that Hart prefers Tolstoy to Dostoyevsky. He qualifies this as an aesthetic opinion: Tolstoy is a better novelist--produces better art--than Dostoevsky, though the latter is, in some ways, a more profound thinker.

I agree that Tolstoy has a much more subdued and well-developed style, at least as it comes through in my English translations (my Russian is elementary and poor). And surely Dostoevsky leans much more heavily on cliche melodramatic tropes (e.g., constant psychosomatic fevers). But there is one claim Hart has made that irks me: that Dostoevsky's characters are less real, or more "unreal" and "cartoonish," than Tolstoy's.

Psychological Unreality and Fleshing Out Characters

By "unreal," Hart does not simply mean "unrealistic." Rather, it is that Dostoevsky's characters do not seem to be genuine people. They are clusters of ideas and ideologies, "psychological chimaeras" (Hart, 2009) that, when we probe them, appear to have no personal core:

"Dostoevsky, on the other hand, is brilliant wherever extreme effects are called for, but almost hopeless at creating a substantial world around the delightful clamor of his characters’ voices, or at creating a credible psychological personality behind any of those voices." (Hart, 2009)

Though it is hard to analyze precisely, I feel what Hart is saying, and mostly agree. Dostoevsky's characters are almost always more motivated by their philosophical ideas than ordinary desires or personality traits. They seem to lack a core personality, something that underlies their ideas, doubts and convictions. Their emotions are responses to their intellectual worries, and not the other way around. The claim is that, for many of Dostoevsky's characters, if we were to remove their conceptual elements, the character themselves would vanish, or at least be so diminished that they would have little setting them apart from others besides properties like "is to the left of," etc. But a genuine person is much more than their intellectual lives and cognitive processes. For characters who are not primarily intellectually driven, they typically have one or two desires or quirks that define their entire personality and narrative arc. This is, at least, how I understand the charge Hart levies against Dostoevsky.

"But, if we look too closely, we will inevitably come to see that, however brilliantly Dostoevsky has fused together an ensemble of psychological convulsions and habits of temperament in each of these characters, the result of that fusion is in every case a creature that could never exist outside of the novel. One cannot enter into these characters; when one attempts to do so, they dissolve back into multiplicity. Not one of them is as plainly, poignantly, unexceptionally alive as, say, Pierre in War and Peace." (Hart, 2009)

Contrast this with the characters of Tolstoy. Take Constantine Levin, from Anna Karenina: his convictions and ideas shift so much, and so rapidly, that he could not remain the same character unless there was some deeper substratum underlying these cognitive shifts. Levin's social relations are not only detailed and well defined, but his inner person stands out as unique among the other characters. In fact, Levin is not really identifiable with any particular ideology or set of ideas, but seems to be a very real person to the reader. Moody, tense, driven to physical activity, always vibrating with pent up energy in need of direction, painfully honest, desiring family life and, more importantly, someone to love what he loves (regardless of what it is he loves, which morphs over time). The way Levin speaks and thinks feels much different from the other characters; his voice is unique, his set of desires, though overlapping with others, are peculiar to him. Tolstoy also goes into great detail about how Levin is perceived by others, which further defines him for the reader: many find him perplexing, irritating, intimidating, grumpy; others find him charming, passionate and respectable. Each of these perceptions are illustrated not only via exposition, but through Levin navigating different social circles and displaying how he can be all these things to different people. (I could also describe how Tolstoy so wonderfully describes Dolly and her husband, Stepan, in Anna Karenina. Stepan, in particular, has a very particular personality, nicely summarized as his "almond oil smile.")

Compare this to the three brothers of The Brothers Karamazov, Alyosha in particular. The family relations and upbringing (described in Book I) serve as the backstory to each brother and are intended as partial explanations for their present personalities. But these relations have more to do with the worldviews of each family member--and how these views determine their treatment of one another--than the persons themselves. Alyosha is the youngest and, as Dostoyevsky emphasizes, very much like his mother. But this similarity to his mother consists almost purely in his ideological outlook--his attraction to and dependence on religion and the Christian view of the world--and his reactive hypersensitivity. His mother has no identity other than as a pious woman with some sort of fainting disorder. Her disorder, and thus Alyosha's, seems to be a sort of inability to handle stress. But what stresses them out? Observing events that violate their religious values and convictions! Others perceive Alyosha as either a saint or religious idiot. All of Alyosha's struggles are over how to (a) retain his faith and (b) apply his faith. He is quite monolithic, just as Rodion Raskolnikov of Crime and Punishment is driven almost purely by an intellectual conflict between will-to-power nihilism and a moral, religious realism centered around love.

Even when Dostoyevsky's characters are not primarily ideological, their desires are so intense and singular that they function as ideologies. Again turning to The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov is defined by his all encompassing "sensuality," which is shorthand for a strong desire to possess and consume women as both sexual and aesthetic objects. He is surprisingly thoughtful, and sometimes formulates cognitive principles that express his desires, such as "all women, in virtue of being women, are interesting." His desires are so simple and monolithic that they become a way of life for him. Take away this one defining desire, and all his beliefs, values and individualizing traits vanish! The person of Fyodor Pavlovich is essentially reducible to his, ahem, horniness.

Hart basically says that Tolstoy's characters are more real, more believable as individual people. Dostoyevsky's characters appear to be collections of ideologies, not people with ideologies. In short, the most well developed characters in Dostoyevsky are developed as much as some of the least developed characters in Tolstoy (I am thinking here of the wonderful Varenka, from Anna Karenina).

Does Dostoevsky Represent People, or Mental States?

All this is quite understandable, and, I think, substantially correct. Tolstoy is simply better at fleshing out characters in this way.

However, I think it is unfair to call Dostoevsky's characters less real. For one, as Hart notes, Dostoevsky's later novels are centered around a central problem/dilemma and take place over a fairly short span of time. We are primarily interested in Dostoevsky's characters as reacting to such well defined situations. It is an excuse to see how different ideas and extreme, monolithic temperaments react when mixed together and prompted by some sort of conflict.

This leads me to my first idea. In trying times, it can often seem that our personhood is in fact, reduced to certain ideas and convictions. I find it quite realistic for Dostoevsky's characters to be so monolithic and extreme, given that each of them has essentially been in a state of ongoing trauma prior to the start of his novels. When we are absorbed in our work, or find ourselves trying to surmount some sort of painful obstacle, our inner lives can become rather monolithic. I often, after a few days of intense parenting, come to and realize that I am much more than simply a father and enjoyer of babies. When struggling with flare ups of my chronic illness, I spend weeks at a time reduced to prayer and angst, where my entire mind is occupied by religious thought and death. I emerge from illness with the feeling that I must round myself out again.

Indeed, as Hart recognizes, Dostoevsky is a master of describing "extremes:"

"Personally, I prefer not to read Dostoevsky as a psychologist at all, while still acknowledging the genius of his phenomenology of certain extreme states of spiritual perturbation." (Hart, 2009)

This, I think, is right on the money. Dostoevsky excels at creating people who have suffered in some extreme way and, as a result, have been psychologically flattened. His characters have, for various reasons, become their dominant ideologies or monolithic desires. They are all in a highly agitated state of mind, even in their calm moments, and their entire being is caught up in questions of morality, religion and philosophy (or horniness).

But is this a bad thing? Does this somehow make his characters unreal? Hart claims that Dostoevsky's psychological insight is an insight into psychological states, but not into the nature of people. In other words, his characters are really incarnations of certain mental processes and struggles, and not plausible depictions of human beings, who supposedly have more depth:

"And I think Dostoevsky’s reputation as a master psychologist to be more a trick of the light than anything else, an illusion occasioned by the sheer psychological implausibility of his characters (which is so extreme that it appears at times to touch upon some deeper truth, but is really more cartoon than portrait). None of this detracts from the truly brilliant insights in Dostoevsky’s tortured religious meditations." (Hart, 2021)

That is, each of Dostoevsky's characters are portraits of mental events in minds, and not minds themselves. But is this true? Are his representations, when taken as representations of people, cartoonish?

Dostoevsky Represents Real People, Too

I do not think so. Tolstoy surely describes the personhood of your average person much better than Dostoevsky does. But I have yet to find a character in Tolstoy that I feel any personal affinity with--that I feel is a representation of the kind of person I myself am. Frankly, Dostoevsky does a much better job at describing people like me than Tolstoy does.

Do not misunderstand my point here: I am not saying that I dislike Tolstoy's characters, or find that I have nothing in common with them. Rather, I truly feel that my life--inner and outer--is strikingly similar to the fever dream that is Raskolnikov's short journey in Crime and Punishment, or Myshkin's constant struggles in The Idiot.

I recently finished Anna Karenina for the first time, at my wife's recommendation, and was surprised and disappointed (in myself) by my reaction: I did not enjoy the first half very much, and constantly found myself unable to understand what made the characters tick. Why is Levin such a moody bitch? Why do his convictions constantly change? He does not merely doubt, and move between different levels of confidence, but throws himself into different beliefs. How Levin can disbelieve in God and then, suddenly, with little conscious development, pray to God for help? How illogical! Why is Anna not more suspicious of her desires? How does she have the power to lie to herself? Isn't logical and moral inconsistency more painful than unfulfilled desires? What weirdos! How can Dolly entertain the idea of a love affair, and stoop to the level of her husband? Strange!

Then it hit me: these are normal people, who move in an out of crises, and have lives outside their mental sufferings. I feel alienated from them precisely because I feel alienated from virtually everyone I encounter. This is an issue with me, not with the characters' "realness." These characters have goals and ambitions that are not fueled purely by intellectual angst. They enjoy life, and suffer only intermittently, because their sufferings are things imposed on them from without, and not constant turmoil within. They, for the most part, are not at nearly all times worrying about metaphysics and the ever-watchful eye of God. And because this allows them room to breathe, it allows them room to develop, to be rounded out, to be what Hart identifies as "real people" with a variety of different experiences and relations. They can plug in to social circles I find completely alien and repulsive. They can "visit" or "call upon" one another. They can *vomits* make SMALL TALK! I can do none of these things--things that "real people" do, and which shape who they are.

In short, Tolstoy's "real people," though they correspond to many people I know, do not correspond to me. A cartoonish, melodramatic spirit can only be represented by a cartoonish, monolithic character. A person who is so wrapped up in their mental life that they become their ideas, or are so possessed by a single desire that they become one with that desire, can only be depicted by a Dostoevskian chimaera. Yet, Hart, I think wrongly, takes depictions of people like me to not be "real people," but only extreme states of the soul. That is where we disagree, and I suspect it is because Hart and I are very different kinds of people.

I am in constant pain of some sort, mostly psychological and intellectual, and live my life in a fog. I am gnawed at by religious doubt that, in some moments, reduces me to a paralytic, and at others makes me run around and screech. My family and friends think of me as volatile and melodramatic. Most do not understand why I always seem to bring up "pretentious bullshit" in discussions about videogames, and why I see every dispute as approaching a very important philosophical truth. I have obsessive compulsive disorder (diagnosed at a very early age, and re-diagnosed several times as an adult!), and am a recovering hypochondriac. At four years old I became epileptic, and was left with sensory issues as a result. I am constantly anxious, my heart never stops pounding, and without medication I am a mess. Sometimes pop-culture pisses me off so badly that I get stuck in thought-loops where I mockingly repeat things like "I love the Mandalorian! Baby Yoda! Baby Yoda! REE!" or "Pickle Rick! PICKLE RICK!" or “Pardon Jared!” I describe these sorts of mocking outbursts as "scratching the folds in my brain." Suicide always seemed an open option for me, not because I was sad, but because I could not see the point of living if there was no metaphysical grounds for morality. If there were not reasons for everyone to love as I do, then what is the point of loving at all? And since I loved much, this question was horrible. (I began to think this at age 12, though not in these terms). A few years ago, when I read Thus Spoke Zarathustra, I was so morally revolted that I suffered from nausea and could hardly finish it. If Nietzsche appeared before me, I would physically assault him for expressing such horrible, but potentially true, views. While recording my last album, I was so discouraged by certain difficulties that I swore off recording music. It has been almost a decade since I have bothered, and I now hate playing music, which was once so dear to me.

Don't worry, reader! Thankfully, as I have aged, and have forced myself to learn about a wider range of topics, I have calmed down quite a bit.

Being charitable to myself, I like to think that I am a very integrated person, a person incapable of compartmentalizing and, thus, incapable of that kind of falseness I attributed to Anna Karenina. But this also causes me horrible pain, often unnecessarily. I expect others to be like this, too, and have a hard time understanding when they are not. I relate very much to Prince Myshkin, who to a casual reader might appears to be an unrealistic, lopsided figure--not so much a person as an embodiment of Christian ideals taken to an extreme. The entire length of The Idiot is devoted to showing how stressful and disappointing it is to be such a person. In the end, it is revealed that Myshkin was not a monolithic ideal after all, but someone torn between these ideals and his actual emotions and desires. Deeply suspicious of his emotions, and choosing, perhaps wrongly, to live and delight only in his ideals, Myshkin makes many mistakes, and acts without prudence. He is constantly disappointed and seen as mentally deficient. (Not to say I am nearly as pure and good as Myshkin--I sadly see myself most in Stepan Trofimovich...)

Towards the end of Anna Karenina, Levin's suicidal ideation involves a spiritual crisis Dostoevsky might have written about. But when written by Tolstoy, it is poorly written, lacking believability and detail. How a man can be truly suicidal due to intellectual and spiritual worries and yet discard those worries so easily? Levin distracts himself, but it seems implausible to me that such a man could do so, once he has been stricken so deeply by this angst. He is somehow tortured and yet so lighthearted that he can ignore this torture. But would such a state really be a state of torture and angst? Or a disconnected series or vacillations between angst and distracted work? The more plausible development would be that he, able to do easily distract himself, would never have plunged into the depths of existential angst in the first place. He might have regarded it as painful, but not so painful as to crush him and make him wish for death. All that to say, when Tolstoy tries to do what Dostoyevsky does, he does so poorly. Or perhaps not poorly, but as describing a kind of person alien to me.

Of course, all of this is a personal point, and I feel somewhat ridiculous making it, but I am essentially saying that Dostoyevsky's melodramatic cartoons are "real people" just as much as Tolstoy's characters are. Sure, they are not healthy people, but neither are Tolstoy's characters. The sort of characters Dostoevsky writes are all, in some way, broken philosophers. As a broken philosopher myself, I find much more in common with them than any of Tolstoy's characters (with the exception, perhaps, of Nikolai Dmitrich Levin). But, indeed, I am abnormal, and my friends and family are always puzzled by my outbursts and constant suffering, which is basically needless in their eyes. I feel very much alone, and probably always will. Reading Dostoevsky was the first time I felt understood by a fiction author. In fact, at times I wonder if Tolstoy, speaking through Constantine Levin, would have hated me, and regarded me as some sort of ridiculous soul without a coherent center. For some of us, Dostoevsky’s "melodramatic urgency" depicts our inner lives and selves. It is not a "mere trick of the light."

Sources:

Hart, 2009: https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2009/09/tolstoy-and-dostoevsky-and-christ

Hart, 2021:

Yes Tolstoy has the most rare ability to paint a vivid character in his tight clean prose, but Dostoevsky got me through high school. He writes characters that by being in extreme situations reveal their inner states—which are driven by ideology or confusion, or faith—but this was more related to me than other writers characters. I think that the problem not mentioned here by hart is that Dostoevsky is focused on drawing out and unveiling the demons of his age and trying to show how one can escape possession. How many people today aren’t under the influence and ruled by western liberal ideologies or scientism? If only one now could write like him and he’d draw out the undercurrents and deep tensions at work today. The truth is though even if his characters are extreme and placed in an extreme plot: it’s just Dostoevsky’s manner of raising the stakes. From Tolstoy we get a picture of the banality of aristocratic babble and a nuanced picture of 19th century Russia, but Dostoevsky gives us more. He places the reader in a world where the reader is forced to encounter the true stakes of life and might even be shown the possibility of redemption. In high school it was his capacity of seeing a murderer as saveable and the portrait of the suffering love of Sonya that made me think that God could save me and his love can win against the greatest passions.

I agree that Dostoevsky 's characters are tortured whereas Tolstoy's are more relaxed but both are representative of real people. Shockingly, some people are shallow and care only about one thing and never grow into better people. Also, as you say, those in tight places are somewhat pressed into a flatter shape - they are a little obsessed about their immediate situation. I think Tolstoy's work is definitely more polished and his characters reflect the aristocratic side of life whereas Dostoevsky is writing street fiction - it's real and gritty and he really needed the money so he might not have had a lot of time for editing and rewriting. In short, Tolstoy is like the Beatles and Dostoevsky is like the Rolling Stones but both are great!